Franz Liszt (German: [fʁant͡s lɪst]; Hungarian: Liszt Ferencz; October 22, 1811 – July 31, 1886), in modern use Liszt Ferenc[n 1] (Hungarian pronunciation: [list ˈfɛrɛnt͡s]); from 1859 to 1867 officially Franz Ritter von Liszt,[n 2] was a 19th-century Hungarian[1][2][3] composer, virtuoso pianist, conductor, teacher, andFranciscan.

Liszt gained renown in Europe during the early nineteenth century for his virtuosic skill as a pianist. He was said by his contemporaries to have been the most technically advanced pianist of his age, and in the 1840s he was considered by some to be perhaps the greatest pianist of all time. Liszt was also a well-known and influential composer, piano teacher and conductor. He was a benefactor to other composers, including Richard Wagner, Hector Berlioz,Camille Saint-Saëns, Edvard Grieg and Alexander Borodin.[4]

As a composer, Liszt was one of the most prominent representatives of the "Neudeutsche Schule" ("New German School"). He left behind an extensive and diverse body of work in which he influenced his forward-looking contemporaries and anticipated some 20th-century ideas and trends. Some of his most notable contributions were the invention of the symphonic poem, developing the concept of thematic transformation as part of his experiments in musical form and making radical departures in harmony.[5] He also played an important role in popularizing a wide array of music by transcribing it for piano.

Berlioz, the passionate, ardent, irrepressible genius of French Romanticism, left a rich and original oeuvre which exerted a profound influence on nineteenth century music. Berlioz developed a profound affinity toward music and literature as a child. Sent to Paris at 17 to study medicine, he was enchanted byGluck's operas, firmly deciding to become a composer. With his father's reluctant consent, Berliozentered the Paris Conservatoire in 1826. His originality was already apparent and disconcerting -- a competition cantata, Cléopâtre (1829), looms as his first sustained masterpiece -- and he won the Prix de Rome in 1830 amid the turmoil of the July Revolution. Meanwhile, a performance of Hamlet in September 1827, with Harriet Smithson as Ophelia, provoked an overwhelming but unrequited passion, whose aftermath may be heard in the Symphonie fantastique (1830).

Returning from Rome, Berlioz organized a concert in 1832, featuring his symphony. Harriet Smithson was in the audience. They were introduced days later and married on October 3, 1833.

Berlioz settled into a career pattern which he maintained for more than a decade, writing reviews, organizing concerts, and composing a series of visionary masterpieces: Harold en Italie (1834), the monumental Requiem (1837), and an opera, Benvenuto Cellini (1838), a crushing fiasco. At year's end, the dying Paganini made Berlioz a gift of 20,000 francs, enabling him to devote nearly a year to the composition of his "dramatic symphony," Roméo et Juliette (1839). And then, to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the July Revolution, came the Symphonie funèbre et triomphale (1840).

Iridescently scored, an exquisite collection of six Gautier settings, Les nuits d'été, opened the new decade. This was a difficult time for Berlioz, as his marriage failed to bring him the happiness he desired. Concert tours to Brussels, many German cities, Vienna, Pesth, Prague, and London occupied him through most of the 1840s. He composed La Damnation de Faust, en route, offering the new work to a half-empty house in Paris, December 6, 1846. Expenses were catastrophic, and only a successful concert tour to St. Petersburg saved him.

He sat out the revolutionary upheavals of 1848 in London, returning to Paris in July. The massive Te Deum -- a "little brother" to the Requiem -- was largely composed over 1849, though it would not be heard until 1855. L'Enfance du Christ, scored an immediate and enduring success from its first performance on December 10, 1854. Elected to the Institut de France in 1855, he started receiving a members' stipend, and this provided him with a modicum of financial security. Consequently, Berliozwas able to devote himself to the summa of his career, his vast opera, Les Troyens, based on Virgil's Aeneid, the Roman poet's unfinished epic masterpiece. The opera was completed in 1858. As he negotiated for its performance, he composed a comique adaptation of Shakespeare's Much Ado About Nothing, which met with a rapturous Baden première, on August 9, 1862. Unfortunately, only the third, fourth, and fifth acts of Les Troyens were mounted by the Théatre-Lyrique, a successful premiere, on November 4, 1863, and a run of 21 performances notwithstanding. This lopsided production stemmed from a compromise (bitterly regretted by the composer) that Berlioz had made with the Théâtre-Lyrique.

Though frail and ailing, Berlioz conducted his works in Vienna and Cologne in 1866, traveling to St. Petersburg and Moscow in the winter of 1867-1868. Despondent and tortured by self-doubt, the composer received a triumphant welcome in Russia. Back in Paris in March 1868, he was but a walking shadow as paralysis slowly overcame him.

Composer, conductor, virtuoso, novelist, and essayist, Carl Maria von Weber is one of the great figures of German Romanticism. Known for his opera Der Freischütz, a work which expresses the spirit and aspirations of German Romanticism, Weber was the quintessential Romantic artist, turning to poetry, history, folklore, and myths for inspiration and striving to create a convincing synthesis of fantastic literature and music. Resembling the Faust legend, Der Freischütz (the term suggests the idea of an marksman relying on magic) is a story of two lovers whose ultimate fate is decided by supernatural forces, a story which Weber brings to life by masterfully translating into music the otherworldly, particularly sinister, aspects of the narrative. Weber's additional claim to fame are his works for woodwind instruments, which include two concertos and a concertino for clarinet, a concerto for bassoon, and a superb quintet for clarinet and string quartet. Born in 1786, Weber studied with Michael Haydn and Abbé Vogler. Appointed Kappelmeister at Breslau in 1804, he gained fame as an opera composer with the production, in 1811, of Abu Hassan. In 1813, he became director of the Prague Opera. In Prague, where he remained until 1816, Weber developed a mostly French repertoire, taking an active, and highly creative, part in the practical aspects of opera production. Underlying his often controversial efforts to reform opera production was his ardent desire to create a German operatic tradition. Although there were, indeed, capable composers in the German-speaking lands, the idea of a German opera provoked much opposition, as the public, trained to perceive opera as an exclusively Italian art form, regarded the concept of German opera as a contradiction in terms, despite the existence of a singspiel tradition, brilliantly exemplified by the Magic Flute by Mozart. While Weber's appointment as Royal Kappelmeister at Dresden, not to mention the triumphant production of Der Freischütz (1821), certainly strengthened his position as champion of German opera, his opponents remained unconvinced. Weber's next opera, Euryanthe (1823), failed to repeat the success of Der Freischütz. In Euryanthe, his only opera without spoken dialogue, Weber introduced the device of recurrent themes throughout the entire opera, thus anticipating Wagner. Although Weber brilliantly adapted a variety of harmonic styles and textures to the dramatic narrative, the overall effect was seriously hampered by a rambling libretto, an inept adaptation of a medieval romance already used by Shakespeare in Cymbeline. In 1825, Weber was invited to London. Among the works he was expected to conduct was Oberon, another opera with aShakespearean theme. The librettist, who took the story from Shakespeare's Midsummer Night's Dream, created, in a misguided effort to please the public, an incredible hodgepodge, even more convoluted than Euryanthe, that not even Weber's genius could salvage. Nevertheless, Oberon, which the English public received with admiration, contains much gorgeous music, including examples of lush orchestration and exquisite tone painting. Often performed in concert, the overture is a true Romantic gem. Already in poor health before his London tour, Weber died in the English capital in 1826, shortly after the premiere of Oberon at Covent Garden.

Not much is known about the life of Tomaso Albinoni. He was the eldest son of a wealthy Venetian paper merchant. The family was very well off, and in his adult life Albinoni was financially independent. He thought of himself as an amateur musician. Although completely trained in his art, he did not seek professional employment in music. He was a fine performer on the violin, and one of the most prolific writers of the violin concerto in the high Baroque. Initially Albinoni attempted to compose church music, but did not meet with much success. However in 1694, with the publication of 12 trio sonatas and the production of his opera Zenobia, Regina de Palmireni, Albinoni had found his milieu. For the rest of his life he would compose cantatas, operas, instrumental sonatas and concerti. His operas were popular throughout Italy, and are very original, although not well known today. In 1705, he married the soprano opera singer Margherita Rimandi. Together they had six children, while she continued with her singing career. Tomaso Albinoni meanwhile had inherited a portion of his father's estate, and began a singing school. In 1722, he published a collection of 12 concerti. He also was invited to Munich where a production of his opera I veri amici was given as part of the festivities honoring the marriage of the Prince Elector to the daughter of the Emperor. This occurred at perhaps the height of Albinoni's fame.

http://www.allmusic.com/artist/tomaso-albinoni-mn0000058485

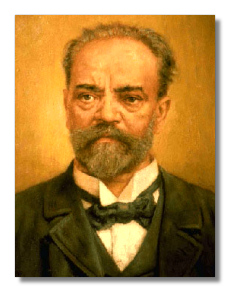

1841 - 1904)

Contrary to legend, Antonín Dvořák (September 8, 1841 - May 1, 1904) was not born in poverty. His father was an innkeeper and butcher, as well as an amateur musician. The father not only put no obstacles in the way of his son's pursuit of a musical career, he and his wife positively encouraged the boy. He learned the violin and finally was sent to the Prague Organ School, from which he emerged at age 18 as a trained organist and immediately plunged into the life of a working musician. He played in various dance bands, usually as a violist. One of his groups became the core of the Provisional Theater orchestra, the first Czech-language theater in Prague, and Dvořák was appointed principal violist. Around this time, he also began giving private piano lessons, eventually marrying one of his students.

During this early period, he composed a ton of music, learning how through studying scores mainly by Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Liszt, and Wagner. At first, his music resembles that of Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert. The quality varies in this music, as you would expect, but the sheer amount of it impresses you. Furthermore, if some of it shows awkwardness, it also shows imagination and inventive tunefulness. In addition to songs and miniatures, you find a great deal of chamber music, at least one opera, and a concerto. Toward the end of this apprenticeship, Liszt and Wagner dominate, although Dvořák still tries to contain them in classical forms. The big work of this phase is the Symphony No. 1, which the composer thought had perished in a fire. In later life, he told his composition students that he had irretrievably lost his first symphony, his students asked anxiously, "What did you do?" "I sat down and wrote another one," he replied. Fortunately, it turns out that this composition wasn't lost, merely misplaced, and we can now hear this milestone in the composer's development. The Wagner phase, however, was brief, about five years. It permeates the opera The King and the Charcoal Burner (1873). The opera was taken off the schedule of Prague's Provisional Theater, due to rehearsal difficulties. Far from sinking into discouragement, Dvořák began a thorough reassessment of his artistic direction, finding his mature path of combining Czech folklore with classical forms. He revised The King and the Charcoal Burner, resubmitted it to the theater, and enjoyed a successful premiere in 1874. Other major works of this period include the Stabat mater (1877), the symphonies 4-6, the serenades for strings and for winds, the violin concerto, and the enormously successful first set of the Slavonic Dances.

In 1874, Dvořák applied for and received a grant from the Austrian government. He applied successfully three more times. Apart from easing Dvořák's financial stress, the grants also brought him to the attention of Brahms, one of the members of the jury. Brahms immediately became a fan and persuaded his own publisher, Simrock, to take up Dvořák's music. Thus began Dvořák's career outside Czechoslovakia. He certainly became the big musical deal within his home country.

Part of the spread of his music derives from Austro-German politics of the time. Bans were placed periodically on performances of Czech composers within the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Scheduled performances of major works like the Sixth Symphony were cancelled in Vienna. However, in 1883, Joseph Barnby invited Dvořák to London to conduct his Stabat mater. The British went crazy for the music, and Dvořák's international career dates from this visit. He returned to England eight more times. His reputation was large enough to attract the notice of George Bernard Shaw, one of the finest of all musical critics. Unfortunately, Shaw disliked Dvořák's music for many of the same reasons he advanced against Brahms.

In 1889, Dvořák became a professor of composition at the Prague conservatory. His best student was undoubtedly his son-in-law, Josef Suk. As a teacher, Dvořák was no wizard of technique. In fact, he insisted that his students have a finished technique before he allowed them into his class. He would criticize student scores, put his finger on weak passages, and in general treat his pupils as colleagues, insisting that they find their own way, as he had found his.

Jeannette Thurber, a wealthy American music patron, in 1892 offered Dvořák a position as artistic director and composition professor at New York's National Music Conservatory, at a salary of $15,000, twenty-five times what he got in Prague. It was also clear that the Americans expected him to help pave the way for an "American" musical style. Dvořák took this last charge to heart. This inaugurated Dvořák's "American" phase, which produced his Ninth Symphony "From the New World," the String Quartet #12, the cantata The American Flag, and the String Quintet in Eb. However, financial advantage and high artistic purpose competed with simple homesickness in Dvořák's soul. Summer vacations among the Czech-speaking community in Spillville, Iowa, helped, but the longing to return to Prague grew. Dvořák wrote almost as many works celebrating his native country as those which hymned the New World: for example, the Te Deum and the cello concerto (one of the best for the instrument). Furthermore, Dvořák had become increasingly interested in streamlining classical forms. In the 1880s, he had entered a so-called second nationalist phase, in which Czech folk elements are completely absorbed and put in the service of Dvořák's formal experiments. The image of Dvořák as some spontaneously musical "holy fool" doesn't hold up in the presence of scores full of formal sophistication. The cello concerto, for example, provides an heroic part for the cellist without burying him in the orchestral mass. Examination of the score reveals tremendous planning to unleash orchestral power while keeping the orchestra out of the way of the soloist. No less a composer than Brahms, who had written his double concerto in 1887 in part as a solution to the problems of the cello as solo instrument, exclaimed, "Why on earth didn't I know that one could write a cello concerto like this? If I had only known, I would have written one long ago!"

A major economic depression in the 1890s reduced the Thurber fortune. She felt she could no longer keep her commitment to pay Dvořák's salary and indeed owed the composer money. Dvořák and his family returned to Prague. This inaugurated Dvořák's final period dominated by tone poems (The Water Goblin, The Noon Witch, and The Golden Spinning-Wheel, among others) and opera (Rusalka, The Devil and Kate, and Armida). Dvořák considered himself primarily a dramatic composer, although, so far, few have agreed with this assessment. He wrote more operas (11) than symphonies, but only two – Rusalka and The Devil and Kate – have been staged with even minimal frequency outside Czechoslovakia.

Nevertheless, Dvořák remains the great 19th-century Czech composer – truly international, building on the achievement of Bedřich Smetana, and outstanding in symphony, concerto, symphonic overture, and chamber music. ~ Steve Schwartz

http://www.classical.net/music/comp.lst/dvorak.php

http://www.classical.net/music/comp.lst/dvorak.php

Born in Hamburg into a Lutheran family, Brahms spent much of his professional life in Vienna, Austria, where he was a leader of the musical scene. In his lifetime, Brahms's popularity and influence were considerable; following a comment by the nineteenth-century conductor Hans von Bülow, he is sometimes grouped with Johann Sebastian Bach and Ludwig van Beethoven as one of the "Three Bs".

Brahms composed for piano, chamber ensembles, symphony orchestra, and for voice and chorus. A virtuoso pianist, he premiered many of his own works; he worked with some of the leading performers of his time, including the pianist Clara Schumann and the violinist Joseph Joachim. Many of his works have become staples of the modern concert repertoire. Brahms, an uncompromising perfectionist, destroyed some of his works and left others unpublished.[1]

Brahms is often considered both a traditionalist and an innovator. His music is firmly rooted in the structures and compositional techniques of the Baroque and Classical masters. He was a master ofcounterpoint, the complex and highly disciplined art for which Johann Sebastian Bach is famous, and of development, a compositional ethos pioneered by Joseph Haydn, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Ludwig van Beethoven, and other composers. Brahms aimed to honour the "purity" of these venerable "German" structures and advance them into a Romantic idiom, in the process creating bold new approaches to harmony and melody. While many contemporaries found his music too academic, his contribution and craftsmanship have been admired by subsequent figures as diverse as Arnold Schoenberg and Edward Elgar. The diligent, highly constructed nature of Brahms's works was a starting point and an inspiration for a generation of composers.

Tchaikovsky was born into a family of five brothers and one sister. He began taking piano lessons at age four and showed remarkable talent, eventually surpassing his own teacher's abilities. By age nine, he exhibited severe nervous problems, not least because of his overly sensitive nature. The following year, he was sent to St. Petersburg to study at the School of Jurisprudence. The loss of his mother in 1854 dealt a crushing blow to the young Tchaikovsky. In 1859, he took a position in the Ministry of Justice, but longed for a career in music, attending concerts and operas at every opportunity. He finally began study in harmony with Zaremba in 1861, and enrolled at the St. Petersburg Conservatory the following year, eventually studying composition with Anton Rubinstein.

In 1866, the composer relocated to Moscow, accepting a professorship of harmony at the new conservatory, and shortly afterward turned out his First Symphony, suffering, however, a nervous breakdown during its composition. His opera The Voyevoda came in 1867-1868 and he began another, The Oprichnik, in 1870, completing it two years later. Other works were appearing during this time, as well, including the First String Quartet (1871), the Second Symphony (1873), and the ballet Swan Lake (1875).

In 1876, Tchaikovsky traveled to Paris with his brother, Modest, and then visited Bayreuth, where he met Liszt, but was snubbed by Wagner. By 1877, Tchaikovsky was an established composer. This was the year of Swan Lake's premiere and the time he began work on the Fourth Symphony (1877-1878). It was also a time of woe: in July, Tchaikovsky, despite his homosexuality, foolishly married Antonina Ivanovna Milyukova, an obsessed admirer, their disastrous union lasting just months. The composer attempted suicide in the midst of this episode. Near the end of that year, Nadezhda von Meck, a woman he would never meet, became his patron and frequent correspondent.

Further excursions abroad came in the 1880s, along with a spate of successful compositions, including the Serenade for Strings (1881), 1812 Overture (1882), and the Fifth Symphony (1888). In both 1888 and 1889, Tchaikovsky went on successful European tours as a conductor, meeting Brahms, Grieg, Dvorák, Gounod, and other notable musical figures. Sleeping Beauty was premiered in 1890, and The Nutcracker in 1892, both with success.

http://www.classicalarchives.com/composer/3448.html#tvf=tracks&tv=about

http://www.allmusic.com/artist/franz-schubert-mn000069123